The Tyranny of the Minority - and How to Prevent It

Recently I received an email from Iona Italia, editor of Areo magazine, informing contributors that this fantastic liberal outlet would be wrapping up operations, and advising us to republish our posts somewhere else - on Substack for example. I’ve decided to take her advice, and re-post my half-dozen or so Areo pieces - including two articles that appeared anonymously - on here.

This is the second piece I published on Areo, on April 2nd 2019. It reflects my interest in direct democratic innovations as a way of undermining elite ideological and institutional control.

When the internet first became part of mainstream public life, one of the great hopes it seemed to hold up was that of an expansion of democracy. From now on, the great media conglomerates would no longer dominate the conversation. Instead, the public sphere would be irrigated by new voices, the voices of ordinary people. And that’s exactly what happened—partly thanks to social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, which allow people to post their views on pretty much anything, from what to do about Brexit to whether the earth is flat.

But the conclusion that the internet has made things more democratic is less clear than it might seem. As well as allowing more people to have a say, the web has enabled small bands of especially vocal activists to dominate the conversation. And not only that—persistent complaints by activists have even led to books being withdrawn from publication, shows being cancelled and people being sacked.

The number of complainants can often be quite small. For centuries, theorists have worried about the potential of unrestrained democracy to lead to a tyranny of the majority, in which majority groups ride roughshod over the rights of minorities. What we often see today is instead a kind of tyranny of the minority: a system in which a particularly extreme and motivated fraction of the populace can wield outsized power in the face of a majority which is either too indifferent or too scared to oppose it.

The claims of the activist minority often draw much of their strength from a tacit assumption that they represent a far larger body of opinion. Complaints about cultural appropriation, for example, rely on the usually unchallenged idea that one representative of a group can speak for all or most of that group. If someone says, I don’t like white people wearing sombreros, we have no reason to treat it as anything more than an individual opinion. If the claim is instead, As a Mexican, I can tell you that by wearing a sombrero to a Halloween party you’re insulting Mexicans, that might seem to justify further action, even if the crucial claim that all or most Mexicans would care about this isn’t backed up.

But the question of how many people the complainants actually have on their side is even more fundamental than that. That’s because numbers are the only thing that can ultimately adjudicate one of the key principles of liberalism: the harm principle, formulated by J. S. Mill. Put simply, the harm principle states that we should all be able to do whatever we want, as long as it doesn’t harm anyone else. As generations of Mill’s critics have pointed out, what counts as harm is often a matter of interpretation. If I tell a dirty joke in public, and you complain about it, have I harmed you or not? Who’s to say?

The answer, ultimately, is the people. That is, on a pragmatic level, we deal with the ambiguity of Mill’s principle by passing laws which reflect most people’s idea of what constitutes harm. That’s why it’s not against the law to say something with which you might disagree, but it is against the law for you to punch me in the face. The idea that getting smacked in the face constitutes a harm enjoys widespread agreement, whereas the notion that you saying something that I might not think is true constitutes a harm is not something that most people would agree with, at least not at present.

And the procedures we use to make the law are designed to give us a more or less accurate sense of what people’s views really are. In our representative democracies, that means that laws are made through voting, by politicians who have themselves been selected by some method that is responsive to the popular will. Of course, there’s no absolutely perfect way of doing this, and you might well think that the electoral systems that we have at the moment fall especially far short of perfection. But the system is designed to give us a sense of the balance of opinion in society, and some of its slightly unusual features (secret ballot, for example) help it do that better than some of the less formal methods we might turn to.

What other things might help us get a better sense of what people are really thinking? One crucial issue for pollsters is sampling: that is, making sure that they get information from as broad and representative a cross-section of society as possible. They need to do that to get a sense of what the average person is thinking, not just the small sub-set of people who are particularly motivated to speak up on a particular issue. Self-selected polls, which rely on people coming forward, are widely seen as junk for precisely this reason. The people who step forward voluntarily may well have a heartfelt view to express, but they may also make up only a tiny fraction of the population.

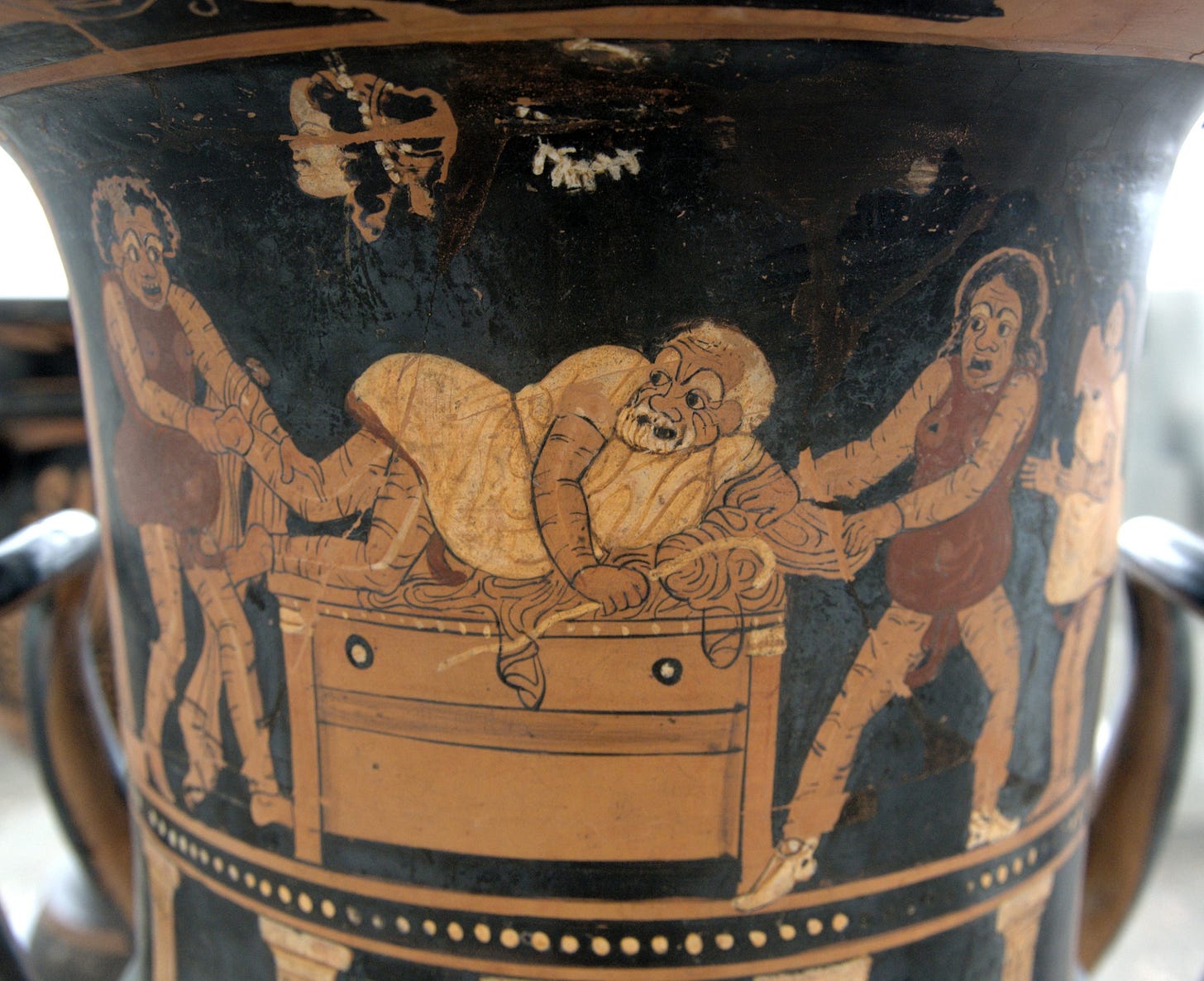

Of course, all this assumes that what we should care about is the number of people who want something, not how much they want it. That assumption has long been a bedrock assumption of our democracies, but we could run our affairs a different way. Various historical societies have relied on voting procedures that take account of the intensity of people’s feelings as well as their number. In the assemblies of some Celtic tribes, for example, warriors would vote by banging their weapons together, with victory going to the side that produced the most noise. In ancient Sparta, some officials were chosen by having people shout for the candidate they liked the most. Obviously, this made it possible for the side that was smaller in terms of number, but more passionate about their cause, to win the day.

But, if the scarcity of societies that still use such methods isn’t indicative enough, we might recall that there are very good reasons why we make decisions based purely on how many people like a certain option, not on how strongly its supporters feel about it. With one person one vote, there’s no possibility that anyone will be able to get more power than anybody else (at least as far as the vote is concerned). If intensity of feeling is allowed into the picture, people might start to become more passionate just to steal a march on their opponents. That would create an unhealthy dynamic in which voters were incentivized to become ever more zealous about their own viewpoints. It might also mean that moderate, unexciting policies would lose out to options that got some people’s blood up. And, crucially, people who didn’t feel as passionately about issues would have less of a say, meaning that it would be more difficult to call a system like that democratic.

Arguably, though, such a system is already in place in certain areas of public life. Not at the level of the state, of course—there, the formal procedures of representative democracy still hold sway. But, in our everyday lives, especially in the world of culture, a less formal system has apparently grown up, on the social media sites that once seemed to hold so much promise for democracy. Which books get published (or withdrawn), who gets hired (or fired) as a presenter and so on—decisions on questions like these are increasingly influenced by self-selected minorities, who accrue authority not through their numbers, but through the intensity and persistence of their complaints.

What do those of us who care about democracy do about this? One thing we can do is try to figure out, before responding to a complaint, whether it actually commands broad support or not. So, for example, a comedy club might get a complaint about an offensive act. Fair enough—what constitutes offensive is about as ambiguous as what constitutes harm. So let’s allow the people to decide: in this instance, the audience for that particular act. How many of them agree that it was offensive?

It may seem like a chore to reach out to every audience member and ask them all. But the alternative is that a club is rushed into taking action because a tiny minority of the audience felt strongly. That will lead to the kinds of problems that we’ve already seen come with self-selected politics: it encourages extremism and ignores the average audience member’s desires. It will also have costs for the comedian who has action taken against him, for the culture of contemporary comedy more broadly—and, in all likelihood, for the bottom line of the club. After all, if a club takes action against someone whom 90% of the audience thought was funny, that will hardly be good for business.

That just underlines how important it is to get these things right. But is it really practical to ask every audience member what they thought of a joke? Well, yes—in fact, the same advances in technology that have made it so much easier for people to make complaints should also make it easier for us to ask others how they felt. All we have to do is make use of them. So, for example, a theatre could, in the case of a serious complaint, use its record of ticket purchases to send a quick survey to everyone who was there on the night in question via email or social media. If a majority of the audience agree with the complaint, the theatre might take action; if not, it could reject the complaint with the added authority of the majority will.

Still skeptical? If so, it’s worth bearing in mind that something of this sort has been going on for a while. What is a counter-petition, if not an attempt to show that more people oppose a change than support it? Some companies have started trying to gauge the broader public’s views on certain issues in a more systematic way: for example, a US radio station recently put the wintertime classic “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” back onto its playlist after running a poll that found that 95% of respondents had no problem with the song. (It had previously been labeled problematic). Of course, petitions and polls, if sloppily designed, can fall into the same self-selection trap that we’ve been discussing. Which is why I’m suggesting we try to design procedures that can give us a quick but accurate picture of what people’s actual views are in these types of cases.

Nothing I’ve said here should be taken to imply that people who want to make a complaint about something don’t deserve to be heard. Of course they do—but, unless they can demonstrate criminal wrongdoing, they have no automatic right to have their complaint acted upon. In our democratic societies, politics and culture should be shaped by what all of us want, not by the whims of a few particularly riled-up activists. The tyranny of the minority has made too many inroads already. Allowing it to continue would constitute a serious erosion of our democratic culture. The way to defeat it is not to try to roll back or place limits on the cacophony of voices that the internet has made possible. It is, instead, to use the technology we now have at our disposal to make sure that it’s the people’s wants that become reality. What we need, in other words, is not less democracy, but more.