One of the best chapters of Salvatore Babones’ book Australia’s Universities: Can They Reform? (2021) asks whether an over-emphasis on university rankings - and world rankings in particular - is ‘warping university priorities.’ Babones’ answer is ‘Yes,’ and a lot of what he has to say is an indictment of the way Australian universities have chased star researchers at the expense of ordinary academics, research at the expense of teaching, and scientific research at the expense of humanities scholarship.

In my other job as a higher education researcher focussing on New Zealand universities, we’ve started developing a theory about a distinctively Australasian model for universities - a model which includes internationally high ratios of general to academic staff, stratospheric numbers of international students, and a relatively high ratio of teaching staff to students.

I may come back to the role of rankings in all this as part of that other job. One important mechanism in the Australasian model, I suspect, is vice-chancellors focussing on Chinese rankings in order to attract Chinese students, and as a result feeling very comfortable blowing out class sizes (something the Chinese rankings don’t penalize). Since this Substack has (nominally at least) a classical theme, though, what I want to highlight in this post is the role that world university rankings are playing in the ongoing decline of the humanities (including, of course, the Queen of the Humanities, classics).

I’m aware that I’m not the first person to point out how world rankings and citation metrics do an awful job of capturing scholarly achievement in the humanities, and nor is Babones. But I do think his account does a good job of showing how what look like obvious sources of bias still persist, even after most of the rankings have made efforts to normalize their citation metrics by subject (that is, to control for the fact that humanists tend to cite a lot less than scientists).

The Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU), compiled by the Shanghai Ranking Consultancy and launched in 2003, was the first global ranking of universities and is still widely influential (especially, it would seem, with those Australasian vice-chancellors chasing after the Chinese student dollar, or rather yuan). The ARWU’s limitations when it comes to humanities subjects are most readily observed by looking at the list of academic subjects that it covers.

If anyone else can see the section for the humanities, or even just a single humanities subject that has somehow strayed into the social sciences, let me know. In the meantime I will assume that it’s not that I’m going blind, but that the Shanghai Ranking Consultancy has, for whatever reason, a blind spot big enough to house all of the humanities disciplines that form such an integral part of universities across the world.

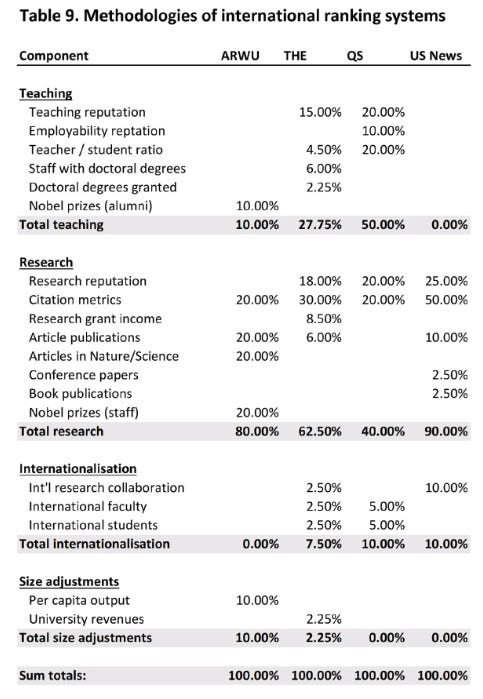

As if leaving the humanities out entirely didn’t bias their rankings against the humanities enough, the AWRU also allocates 20% of its total score to articles in Nature and Science (both science journals), and gives extra credit for Fields Medals (in mathematics) and for Nobel Prizes, which are heavily skewed towards the sciences. Just to make sure that universities’ achievements in humanities fields have absolutely no bearing on their world ranking, the AWRU also specifically ignores the Nobel Prizes in literature (and, for what it’s worth, peace), meaning universities only get credit for prizes in the physics, chemistry, and medicine categories.

Other major world rankings, like the Times Higher Education and Quacquarelli Symonds rankings, do take more academic fields into account. What they don’t take into account are books (at least, they don’t give direct credit for books in the way they do for articles; books may boost universities’ citation metrics). Now, I would be one of the last people to argue that producing a book is the be-all and end-all of humanities scholarship, but it’s clearly a type of contribution that deserves to be recognized. It’s also a type of output that is much more prominent in humanities than in science fields, and takes up correspondingly more of humanists’ time.

A final source of persistent bias against the humanities in these world rankings is the yearly Highly Cited Researchers list drawn up by Clarivate Analytics and drawn on by the ARWU. The list is based mainly on the Science Citation Index and the Social Science Citation Index which, as their names suggest, don’t include humanities scholars. Unsurprisingly, then, the most ‘highly cited researchers’ are almost always scientists. This, in turn, means that only science (and social science) programmes can contribute to their universities’ HCR score in world rankings.

Clearly, since classics is a humanities discipline, all of this is bad for classics. Unfortunately, things only get worse if you look for classics in the rankings’ disciplinary breakdowns. The humanities do at least have a presence in the THE rankings, in the form of a broad ‘arts and humanities’ category. This category can be further broken down into a number of sub-categories called archaeology; architecture; art, performing arts & design; data science (?); history, philosophy; history, philosophy & theology; and language, literature, and linguistics. My guess would be that classicists’ research outputs are included in one (or several) of these categories, though the field isn’t accorded the dignity of being named (unlike, say, history and philosophy, which for some reason headline two of the sub-categories).

The US News rankings only seem to have the broad ‘arts and humanities’ category, without any way that I could see to slice that pie any further, even if the science pie appears to have been sliced into some exceedingly fine sections. (‘Cell biology,’ ‘condensed matter physics,’ and ‘endocrinology and metabolism’ all have their separate categories on the same footing as the whole of ‘arts and humanities.’)

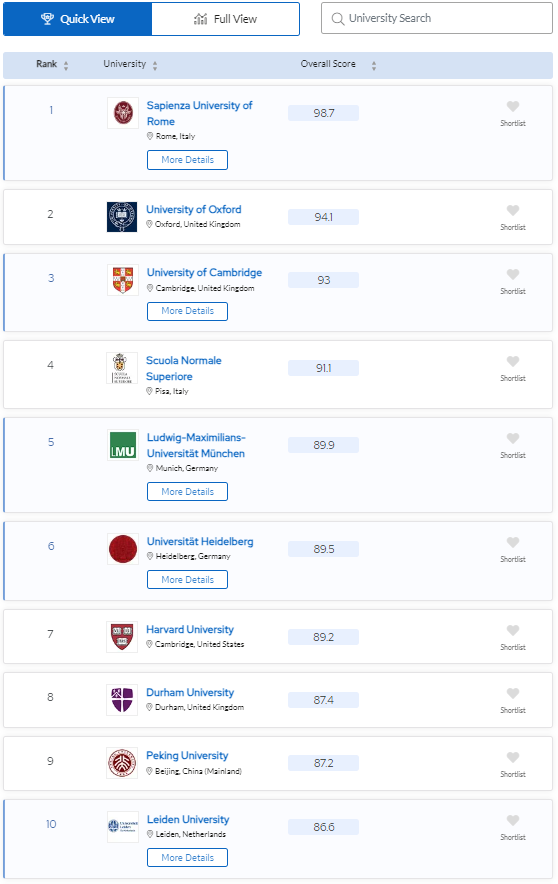

The QS rankings, though, do buck this sorry trend of acting as if historic humanities disciplines like classics don’t exist. If you go to their breakdown by subjects, they actually have a number of sub-categories within the humanities that are recognizable to people who have a BA (and there are still quite a lot of us!) Here, among other important fields (like history and philosophy), you will find a sub-category called ‘classics and ancient history.’ And if you click on it, this is what you will see:

I actually find this a reassuring list, since it tracks my own sense of where the best work is being done in my field reasonably well. I’m a little surprised to find La Sapienza quite so high up, though this may reflect the fact that I’m a Hellenist rather than a Romanist; and to see no French universities in the top 10, though there are two French universities in the top 20. My own interest in ancient Greek democracy and political institutions made me expect to see the likes of Stanford, Edinburgh, and Copenhagen higher up, but obviously there’s much more to classics than my own specialism, and Stanford and Edinburgh do place reasonably well anyway (at 16th and 26th respectively).

But the metrics they’re using have clearly recognized that classics is one of the only fields in which European universities still hold their own against the top Anglo-American ones - not surprisingly, of course, if we remember that these are the European classics that we’re talking about, and people who grow up among the ruins of the classical world are probably going to be more interesting in studying it. There’s even a place for Peking University in the top 10 (and other Chinese universities lower down the list), suggesting that these metrics have also managed to reward institutions that do good work in non-Western classics and ancient history. (Some of this may also be due to recently established departments, like Peking’s Center for Western Classical Studies, that focus on the Western classics).

Some proportion of the subject rankings (as for the overall rankings) seem to stem from reputation, usually assessed simply by asking other academics about other departments in their field. This is obviously a little circular, but the assumption that academics’ views of departments in their field will track more objective features of those institutions may be a fair one. The subject rankings also integrate a measure of employer reputation, for which the views of employers are solicited. It doesn’t seem out of the question that European classics departments profit here from the higher cultural prestige of classics in European societies; whether they should (because universities that invest in the subjects their societies value should be rewarded for that, say) brings us into some ultimately quite philosophical questions.

The main point of this post, though, is that the world ranking systems discussed above still don’t do a fantastic job of tracking achievement in humanities research. The ARWU completely excludes the humanities, while the other world rankings don’t give credit for books on an equal basis with articles and rely on a list of ‘highly cited researchers’ which excludes humanists from the get-go. As for classics in particular, the QS rankings seem to be pretty good at ranking classics departments; but none of the other ranking systems even has a category for classics.

To the extent that university administrators are paying attention to these rankings, all of this is bad news for the humanities. If university administrators are keen to climb rankings in which the humanities count for less than other fields, they will be less likely to allocate funds to the humanities rather than to other parts of the university.

What follows? Only that humanists and humanities organizations might make more noise about their - to use a humanities term - systematic erasure from rankings like the ARWU. It might make sense not only to raise awareness of world rankings’ humanities blind spot, though, but also to raise questions when your university celebrates a climb up any of these particular ladders. Classicists might want to encourage their institutions to pay more attention to the QS rankings in particular - on the quite reasonable grounds that it actually does a better job at measuring the research that classicists are producing.

Helping universities choose rankings that more accurately reflect the real productivity of scholars employed in different fields won’t solve the crisis in the humanities on its own, of course, nor will it provide a panacea for classics. But as part of a broader, multi-pronged strategy (alongside more public engagement, say, and less ideological solipsism) it might just help improve things in disciplines that were once at the heart of the university project.