Late last year a friend sent me this post by New Zealand political commentator Matthew Hooton, in which he declares that he’s ‘not one of those who worries the universities have become bastions of postmodernism and enemies of free speech,’ that he personally has ‘never once felt constrained in what I can say,’ and that he preferred the days when ‘the political right used to pride itself on being the intelligent side of politics’ (something Hooton seems to think is inconsistent with criticizing today’s universities). Unfortunately for Hooton, he is running up against a now quite considerable body of evidence - much of it consisting of surveys of academics themselves - for a chilled atmosphere for free speech at universities. The response I sent my friend in an email got lost in cyberspace for a while, but he has now suggested I post it somewhere. So here it is, with a few links and illustrations added in.

The first thing to say about Hooton's post is that it is entirely anecdotal. That is, it relates what he claims has been his personal experience of one academic discipline at a couple of institutions and a few conferences.

So even if we assume that everything Hooton says in the piece is 100% true, that wouldn't tell us much about the state of free speech at universities.

As it happens, I have much more extensive experience of universities in the UK, the US, and New Zealand than Hooton has, and my experience has been very different. But that is not the point.

To find out what the state of free speech is really like at universities, we need to ask large numbers of academics and students what their experience has been, and consider a broad range of incidents that are relevant to the issue.

Thankfully, a good deal of this kind of work has been done over the past decade or so by think-tanks, NGOs, and other organizations across the English-speaking world. (That universities tend not to be the ones looking at this evidence tells its own story.) I summarized much of this research in my report on academic freedom for the New Zealand Initiative, which came out earlier this year.

This evidence shows that a substantial proportion of academics and students feel uncomfortable discussing controversial topics (like race and sex/gender) in the classroom. It shows that the number of attempts to have academics disciplined or sacked for their views has risen sharply in recent years, as has the number of deplatformings. And it shows that right-of-centre academics and students tend to feel more fearful than their left-of-centre peers.

Hooton might have profited from looking at some of this now extensive empirical literature on this topic before writing his post. For example, he wonders 'what things those who worry about free speech in the universities want to say that they feel they cannot.' The many surveys which have been conducted in universities across the English-speaking world give us a good sense of what people feel they cannot talk about. In New Zealand, the two topics that academics report feeling most inhibited about are the Treaty of Waitangi and sex/gender.

Hooton adds that if the views people are worried about discussing are 'complete nonsense like saying that printing money doesn’t cause inflation or that all Muslims are terrorists then they ought to keep silent unless they have some supporting evidence or argument.' But the problem isn't that people feel fearful of expressing flat-earth theories. It's that they feel fearful of saying that sex is biological, or that Māori ceded sovereignty in the Treaty of Waitangi.

Does Hooton consider those views so nonsensical as to not deserve a fair hearing in a university? If so, it rather qualifies his claims about exploring all aspects of any issue with his students. (I might add that the idea that printing money doesn't necessarily cause inflation is, in fact, one that has recently been extremely fashionable in some segments of academia, where it is known as Modern Monetary Theory. That Hooton doesn’t seem to be aware of this is another sign that he is less au fait with academic life then he wants to pretend.)

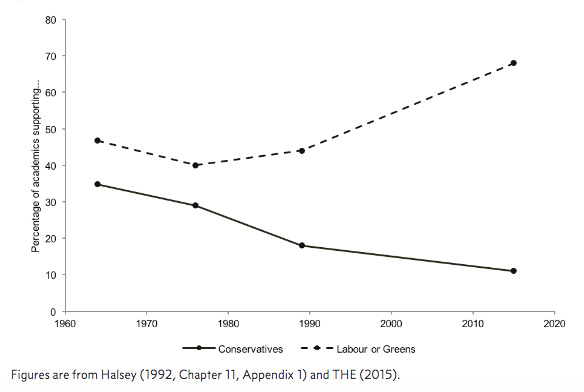

Hooton claims that the reason universities are currently so skewed to the left is because 'right-wing voters are more likely to want to make money than write papers.' Personality differences have been considered in this context, but they are unlikely to explain most (or even much) of the problem, since the ratio of left- to right-wingers at universities wasn't always as large as it is now, and has grown considerably over the past few decades. That has suggested to many that social dynamics are at play (with right-wingers feeling increasingly out of place in academia over time) and not simply more stable factors such as personality differences.

Finally, Hooton says that the idea that academic freedom is under threat at universities is 'based mainly on people who aren’t in them.' Again, this is not something he would have written had he bothered to actually look at the evidence, which includes (in New Zealand alone) hundreds of testimonies from academics, several surveys in which substantial numbers of academics and students say they feel uncomfortable discussing certain topics, and a number of well-documented incidents in which censorship clearly took place (the deplatforming of Don Brash at Massey, to cite just one example).

Hooton ends his post by arguing that the right should go back to 'being the intelligent side of politics.' I would be satisfied if we could go back to the days when political commentators felt a duty to familiarize themselves with the relevant evidence before holding forth on topics of public concern.