Last year I was invited to contribute a chapter on classics to an edited volume about curriculum. Eager to incorporate some of the reading I had been doing for my Honours seminar on Western civilization, what I produced ended up being devoted mainly to summarizing the enormous body of recent research on the West (and especially Christianity’s influence on it), rather than to the topic of classics as part of school or university curricula. Though the editor kindly offered to re-work it with me, we ended up running out of time before a publisher’s deadline. Since I think the overview of recent empirical work on Christianity and the West might be of interest to Owl of Athena readers, I have decided to post the full essay here.

The State of Classics

Classics has a fair claim, alongside philosophy, to being one of the oldest of all academic disciplines. Classics as practiced in the West arguably had its origins in the scholarship of Hellenistic Alexandria, where the texts of Homer, the ‘big three’ Athenian tragedians (Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides), and other canonical authors were edited and analyzed. Copying, editing, and commentating on Greek and Latin manuscripts continued through the medieval period, before experiencing a remarkable flourishing in the time of the Renaissance humanists. Though Greek and Latin had played a central role at European universities since their establishment, classics was eventually re-constituted as a discipline within the modern university following Wilhelm von Humboldt’s reform of the Prussian university system in the early 19th century (Pfeiffer 1968).

For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, classics retained a place at the centre of educational curricula in Western societies, especially at the elite level. In the UK public schools in the tradition of Thomas Arnold continued to place great emphasis on Latin and Greek well into the second half of the 20th century; a similar culture persisted in independent schools in North America and Australasia. On the European continent Latin and Greek maintained a strong presence in the public school system, especially at selective state ‘grammar schools’ such as the German Gymnasium and the Italian liceo. Students still study the classical languages in continental countries in numbers that would now seem unthinkable in Britain.

Recently there has been something of a rearguard action in Britain especially, with the UK government announcing a £4 million programme to introduce Latin to 40 state secondary schools in 2021 (Bryant 2021). In New Zealand, classical studies (taught without the languages) continues to be a popular subject at secondary school level. But there seems no doubt that the trajectory of the subject is downwards, with classics departments facing cuts or outright disestablishment across the English-speaking world, from Roehampton in the UK to Victoria University of Wellington, where I used to teach.

How has classics in New Zealand come to this pass? The decline of classics is part of a broader decline affecting classics and other humanities subjects across the English-speaking world (Schmidt 2018). It is therefore likely that it shares some of the same causes, including the continuing rise of STEM subjects; a preference for degrees that will re-pay increasingly large student loans; and a general decline in the prestige of the humanities.

But classics has also failed to make a compelling case for its continued existence in a way that might at least level the playing field with other subjects that are now competing for space in high school curricula and university budgets. In some ways, this is hardly surprising. Many of the traditional justifications for humanistic study now seem rather careworn. The belief that great literature can be morally improving is no longer widespread; and the decline of traditional high culture has meant that even arguments based on ‘cultural literacy’ have less purchase than they once did. More importantly, though, arguing for the importance of the Western cultural tradition - or even that a Western cultural tradition exists - has over the past few decades come to seem thoroughly disreputable. The idea that modern Western cultures have a heritage that extends to long-ago times and texts is now likely to elicit accusations of racism and even of white supremacism, even as indigenous scholars and activists make use of exactly the same idea (that cultures have deep roots in the past) in advocating for the importance of their preferred subject areas.

In such a context, and in view of the backlash it may elicit, is arguing for the importance of classics to modern Western societies in anything but a deconstructive or skills-based mode even worth the attempt? I am foolhardy enough to believe that it is. It seems clear that the ancient Greek and Roman world can be taught and researched in different disciplinary environments (together with ancient societies, say), and there may well be leeway to re-orient classics departments along these lines at the larger and wealthier classics departments in the US and UK (Kierstead 2021a). In less monied environments, though, the subject is in a fight for its life, and it seems unlikely that a discipline that sees itself as in need of redemption (or at least radical restructuring) will attract much funding, or much support, for long. The only real alternative to a managed decline (almost certainly into eventual oblivion) is to argue for the real importance of the subject in the public sphere.

If the idea of presenting the subject as a kind of self-destruction mechanism seems unpromising, so does the idea of defending it as an inculcator of skills. Classics probably does help inculcate skills in reading, writing, and the like; but if that was the only point of it we would be better off abolishing the subject and teaching students these skills more directly (or, for that matter, using some other material to inculcate the same skills).

The only option is, then, to actually defend the discipline of classics (as well as Latin and Greek) and its relevance in in modern Western societies. Teaching and researching the deep past of Western nations’ European heritage is no more racist than teaching the deep past of their First Nations, native American, or Maori heritage. Nor does defending one of these mean that we should have no place for the other. Indeed, if understanding our cultural past is a worthwhile endeavour, this should apply equally to other cultures; seeing classics as a way of understanding an aspect of ourselves thus complements rather than contradicts one of the most common arguments for more non-Western and indigenous content and perspectives.

Fortunately, we are in a better position now than we have ever been to understand how Western societies developed through the long course of European history. Recent work has pointed to a number of areas in which Western practices were long distinctive, if rarely unique; these range from marriage and family structure through institutions (markets, for example) all the way to particular styles of thought (about time, say). Not all of this research vindicates older, more naïve narratives about Western culture; nor can all the areas of Western distinctiveness it points to be celebrated or seen as a source of pride. Some of it even consigns ancient Greek and Roman culture to a relatively unimportant place in the history of Western civilization, especially compared to the rise of Protestantism, say, in the early modern period.

This recent research does, though, make clear that the basic idea of a Western civilization extending into the European past is not simply an assertion, but is supported by a good deal of evidence. I will draw on some of this evidence, and some of this research, here to suggest that it makes sense for us in Western societies to try to understand the long history of Western civilization, and to inculcate this kind of understanding in our young people. Maintaining a knowledge of the classical civilizations of the West can put us into an excellent position to understand where we have come from, and who we are - for good as well as ill.

The New Research on the Roots of Western Societies

Before surveying the recent research I mention above, though, let us begin with the most obvious area in which subsequent Western civilization was continuous with its Greco-Roman forebears. This is in the sphere of culture. Milton sought to emulate Homer and Vergil. Many of Shakespeare’s plays depend on Plutarch. Descartes sought to overturn Aristotle; the Catholic Church, at least after it decided to embrace the work of Thomas Aquinas, sought to propagate a Christianized version of Aristotle’s thinking. Sculptors like Canova and Rodin looked back to what sculpture survives to us from the ancient Greco-Roman world (largely in the form of Roman marble copies of lost Greek bronze originals). Monumental buildings from Washington to Wellington draw on the forms and motifs of Greek and Roman architecture. Even more obvious – so obvious, in fact, that it can be hard to see – is the debt that modern Western languages owe to Latin and Greek, not least the Romance languages, which evolved out of regional varieties of Latin. Even more obvious, and perhaps even more often missed these days, is the fact that the dominant religion of Western history, Christianity, has its origins in classical times, in the nexus of Jewish and Greek cultures in the Eastern reaches of the Roman Empire.

There is, then, always the argument that some acquaintance with classics is necessary for a baseline level of cultural literacy in any Western culture. Anyone who wants to understand the subsequent literature, philosophy, or art of the West, from the Dark Ages to the modern US, would be well advised to know something, at least, about Greek and Latin literature, philosophy, and art. This knowledge will also be helpful in understanding why English draws a good deal of its scientific terminology from Greek and Latin; why some banks and public buildings look the way they do; and why the scriptures of the West’s most popular religion were written in the languages of the ancient Mediterranean.

Admittedly, the number of neo-classical banks is hardly high enough to occasion any really serious kind of bewilderment in those who have not had the benefit of a classical education. Literary works that deal as directly with the classics as Paradise Lost are probably not much read on beaches these days (or anywhere, for that matter, outside a dwindling number of classrooms). And more modern forms of entertaining that do deal directly with the Greco-Roman past (the blockbuster video game Assassin’s Creed Odyssey, for example, which is set in late fifth-century BC Greece) may be more easily understood or enjoyed without any formal classics background.

With the cultural literacy argument accordingly weaker, it may be helpful to be able to appeal to less obvious manifestations of long-term cultural patterns on modern Western societies. Here there is a need to go beyond what I will call naïve accounts of the Western tradition: those that draw excessively sharp and ultimately rather arbitrary lines around the West (as, for example, Samuel Huntington did in his Clash of Civilizations: Huntington 1996), or that simply assert, without much evidence, a package of characteristics that the West is assumed to have more or less always had (like ‘individualism, liberalism, constitutionalism, human rights, equality, liberty, the rule of law, democracy, free markets, the separation of church and state’ – Huntington again). Victor Davis Hanson’s attempts to find an enduring identity for the West either in family farming (in The Other Greeks) or for a distinctive ‘Western way of war’ (in Carnage and Culture) founder, for their part, on Hanson’s tendency to cherry-pick examples that support his vision of the West without considering whether similar examples might be found in non-Western societies. The idea that Western armies have had a unique tendency to seek out decisive engagement since the Athenians charged Darius’ Persian invasion force at Marathon is a case in point; Hanson fails to recall, it would seem, that ten years after Darius’ invasion his son Xerxes would unwisely seek out a decisive engagement in the straits of Marathon – an engagement that turned out to be a decisive defeat for the Persians.

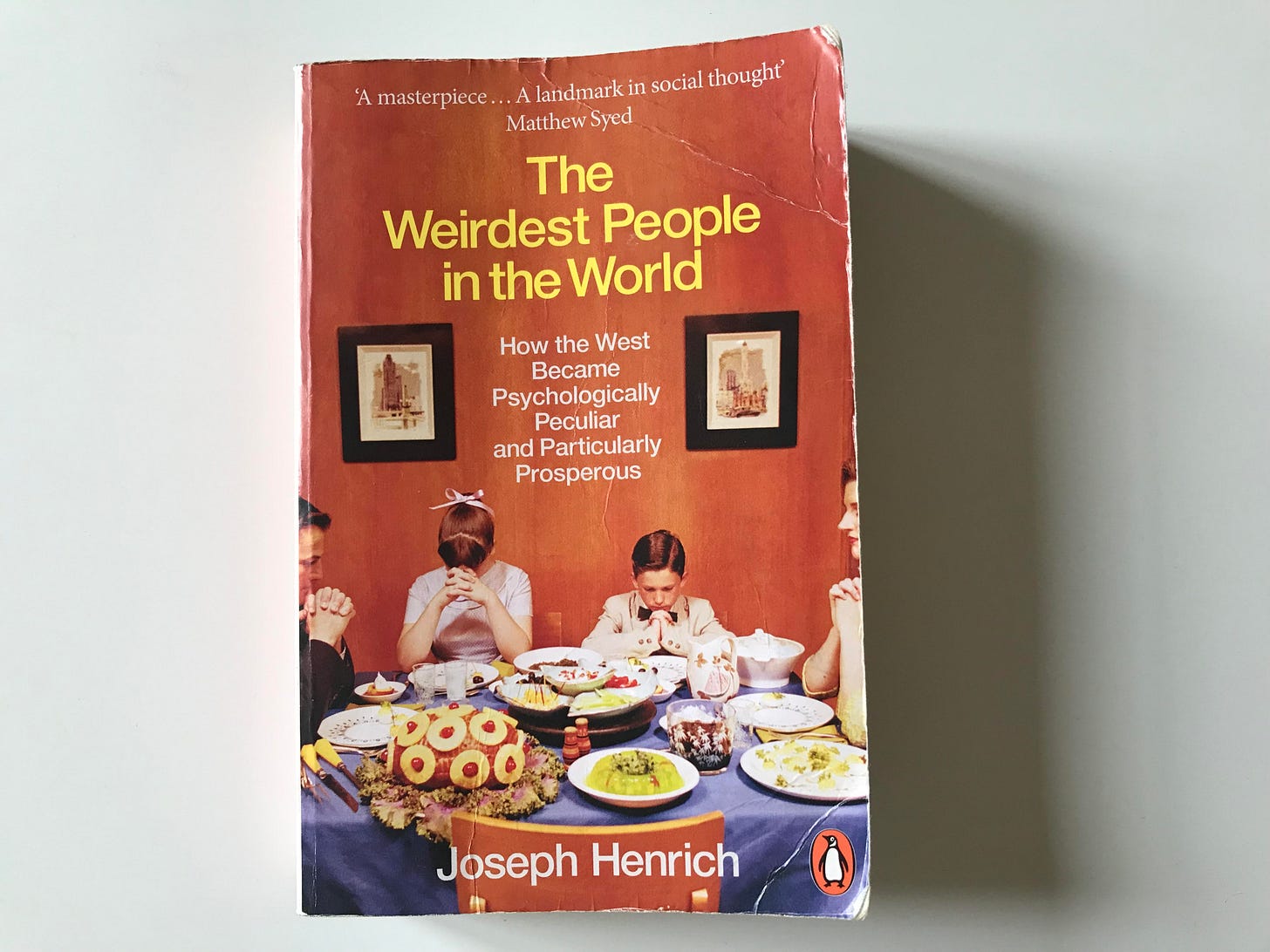

If I have called these accounts naïve, though, it is because in spite of their methodological failings – or even their complete eschewel of any kind of systematic investigative methodology – these older accounts are often more or less correct about the cultural elements that have been distinctively, if not uniquely, present in the West. I believe, to repeat, that recent research upholds some, if not all, of the traditional story about the emergence and the nature of Western civilization. The Christian church really was an influential as high culture might suggest (indeed, it may have been even more so), though mainly through the slightly surprising route of its teachings on marriage and the family. At the same time, an unusually strong tendency towards extra-familial sociability, from associations to the market, really was a feature of the West. So was an inclination to think about things, from the universe to morality, in highly universal and abstract terms, a tendency which surely helped the West arrive ahead at its rivals at the modern scientific and industrial revolutions as well as at the first great revivals of republican and (quasi-) democratic forms of governance. The best summary and compilation of the recent research that I think supports this is Joseph Henrich’s The Weirdest People in the World (Henrich 2020: the title puns on Henrich’s acronym for people from Western, Education, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic - WEIRD - societies), whose account of the distinctive social and institutional path taken by the West I largely follow below.

We can begin, as Aristotle does in his Politics, at the smallest level of social analysis – the family, or even the couple. Families in WEIRD societies are distinctive in five main ways: bilateral descent (with relatedness traced equally through both parents); taboos against marriage to cousins and affines (‘in laws’); an unusually strong emphasis on monogamy (more on which below); being centred on married couples and their children and largely excluding more distant relatives; and neolocal residence, with newlyweds establishing separate households. Though these practices may seem normal to most readers, they are in fact extremely rare, with none of them being observed in over half of the societies listed in the widely-used Ethnographic Atlas, and all five of them being observed in only 0.7% of the societies listed (Henrich 2020, 156-157).

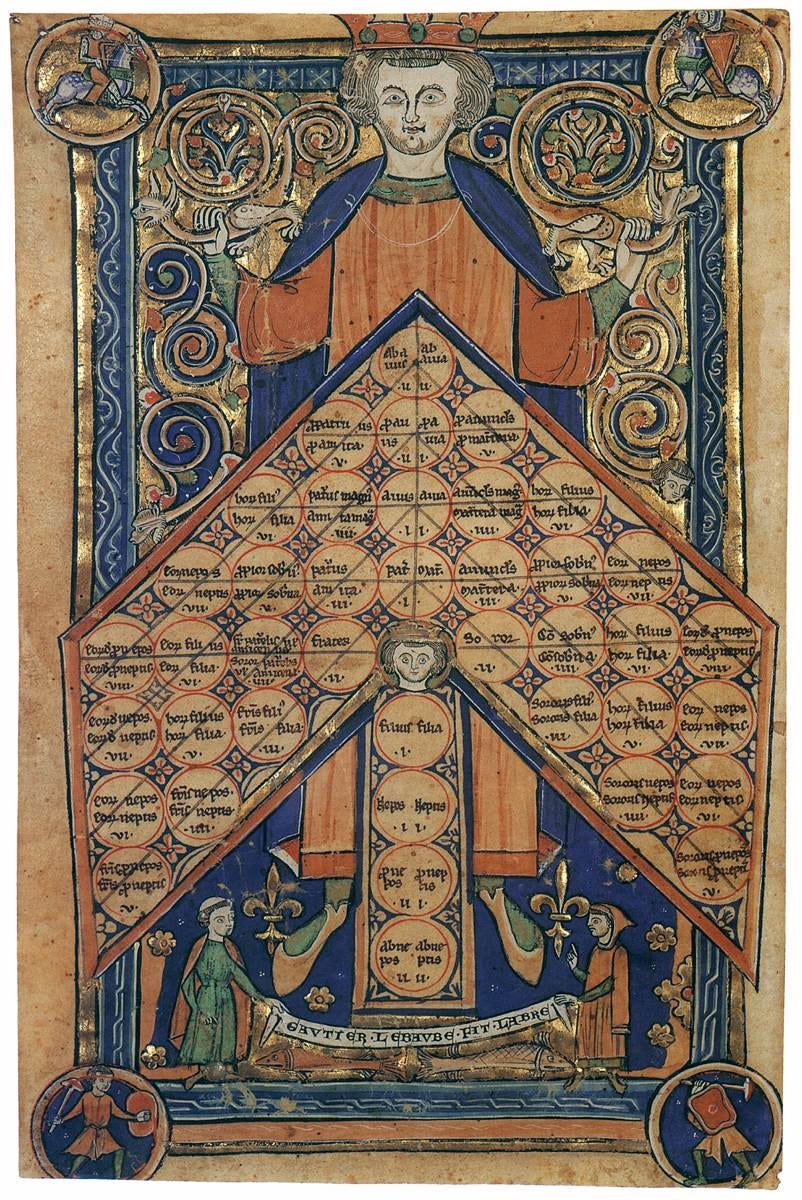

In Henrich’s account, the WEIRD family is a result of what he calls the Marriage and Family Program (MFP) gradually implemented by Christian churches in Europe from the dark ages on. Church leaders prohibited marriage to more than one spouse, marriage to cousins all the way to the sixth degree, marriage to in laws (your brother’s widow, for example), and marriage to anyone in a newly-created category of spiritual affines (godparents and so on). They also strongly discouraged sex outside of marriage, even for men (something which had been tolerated in antiquity), discouraged adoption, suppressed arranged marriage, and encouraged neo-local residence, together with dowries or gifts to help newlyweds set up a new home (Henrich 2020, 165-166).

Henrich’s list of church pronouncements implementing the MFP begins with the Synod of Elvira’s banning of sororate marriage (marrying your deceased wife’s sister) in 305-6 AD, and continues with many similar declarations from the fourth to the early thirteenth century (Henrich 2020, 492-498). The culture which most directly shaped WEIRD families, then, was the institutionalized Christian culture of late antiquity and of the early and high middle ages, especially in the West (with the Orthodox churches implementing a milder version of the MFP, only banning marriage to cousins of the third degree, for example). That would place the roots of the Western family in the last couple centuries of the Western Roman Empire and in the post-Roman dark ages in Western Europe. These periods of Western culture were obviously hugely influenced by the early church, which took its first steps as the Roman Empire was at or near its peak, and ultimately by the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth himself, who lived in the time of Augustus and Tiberius, so there is an argument for locating the seeds of the Western family in the 1st or 2nd centuries AD. In any case, the ultimate origins of the WEIRD family clearly lie in the ancient Greco-Roman world.

One of the key features of the traditional WEIRD family is monogamy. Monogamy is in itself quite rare, with only 16% of the societies in the Ethnographic Atlas described as monogamous. Even the form of loose, asymmetric monogamy that was the norm in Greece and Rome - where women were expected to be faithful, while it was common for men to have sex with slaves or sex-workers - was highly unusual, especially in applying to elite men as well as those lower down the pecking order. Not even elite men in Greece and Rome – highly unusually compared to other ancient societies – could respectably keep concubines at home or have more than one legitimate wife. This already unusually comprehensive form of monogamy was further extended as the Christian church grew in power and influence. The new Christian norm made extra-marital sex unacceptable for men as well as women and emphasized consent and romantic love (all of which is stressed in Tom Holland’s recent popular history of Christianity, Dominion: Holland 2019). This form of monogamy only became common worldwide in modern times, and probably because it was associated with Western economic modernization; polygamy was outlawed in Thailand in 1935, in China in 1953, for Hindus in India in 1955, and in Nepal in 1963 (Scheidel 2009, 281-284).

If Christianity played a major role in intensifying Western monogamy, though, an unusually universal form of monogamy (that is, one that applied to everyone, even elites) was already a feature of the Greco-Roman world. Monogamy may have been stressed in classical Athens (including through legislation in the time of Solon and of Pericles) partly in order to curb aristocrats’ desires to father more legitimate children; and thus monogamy may have helped undergird the city’s strong male-citizen egalitarianism (Lape 2003). Monogamy in republican Rome may have been part of a more general inclination on the part of republican city-states towards monogamy, which can suppress inter-male competition and boost military participation and effectiveness (Scheidel 2009, 288). (Monogamy makes it more likely that lower-status men will find a mate, and also lowers testosterone levels society-wide, since men who have become fathers have lower testosterone: Gettler et al. 2011). Whatever the reason for Athens and Rome’s unusual marriage norms, though, classical Greece and republican Rome seem to be the earliest societies we know of to adopt a form of socially-imposed universal monogamy (Scheidel 2009, 282). And since Christianity grew out of the Greco-Roman world, it may be that the deepest roots of WEIRD monogamy lie not in Christianity, but in the pre-Christian, broadly republican city-states of Greece and Rome.

Even if the West’s highly unusual marriage and family practices were the only sociological inheritance we had from Greco-Roman antiquity, we might already have a good enough reason to study it. But recent research also points towards further effects which flowed from the West’s unusually strong norm of monogamy and from the church’s MFP. The most important of these (since it led in turn to further developments) was that the MFP effectively made it impossible for Europeans to maintain the extended kinship-based networks that were and are a major feature of most non-WEIRD societies. Instead, Europeans were forced to resort to non- or extra-kinship forms of sociability.

The result was an extraordinary proliferation of various forms of non-kinship associations. Monasteries were the first, with these largely self-governing religious communities expanding across Western Europe after Benedict’s founding of Monte Cassino in 529, and more rapidly after the emergence of the Cluniac movement in the 10th century (van Zanden 2009). Guilds also proliferated from the 11th century, with the most rapid growth of guilds in Britain taking place between the 14th and 16th centuries (Ogilvie 2019). Universities also began to spread in the 11th century, slowly at first, but again more rapidly in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries (Verger 1991). The incorporation of largely self-governing cities was another development that began in the high middle ages (around 1100) though in this case the most rapid growth came c. 1200-1400, earlier than in the case of guilds and universities (Henrich 2020, 317). By the age of the Enlightenment, and particularly in the 18th century, it was knowledge societies like the Birmingham Lunar Society (attended by the likes of James Watt and Matthew Boulton) that multiplied across Britain and Western Europe (Mokyr 2002). All of these networks of non-kinship associations boosted extra-familial pro-sociality and facilitated the flow of knowledge outside of clans (the most common site for the passing down of craft techniques in China, for example: de la Croix et al. 2018).

One of the most important of these institutions for interaction with non-kin was the market. Markets became increasingly frequent in Western Europe roughly in tandem with city incorporations which, as we have seen, increased in number particularly rapidly in the 13th and 14th centuries (Henrich 2020, 317). And these markets had effects on Western sociology and psychology. Several studies have found that being more exposed to markets increases impersonal pro-sociality; in other words, it makes people more generous and trusting of non-kin others, and more willing to cooperate with them (Henrich et al. 2010; Agneman and Chevrot-Bianco 2022). Over time it may also increase patience and self-regulation and allow for greater psychological variability in the affected populations (Clark 2007; Gurven et al. 2013).

The extraordinary expansion of non-kin association in the West, then, may have been in part a consequence of the social beliefs and practices inculcated by Christian churches from late antiquity into the middle ages. If that is right, it should come as no surprise that the emergence of a new form of Christianity during the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century also had an enormous impact on WEIRD societies.

One of the major ways in which Protestantism may have influenced the West is by increasing industriousness. This was, of course, Max Weber’s thesis in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904). And there was certainly an increase in industriousness from the 17th century on (at the latest) that we need to explain, with some historians even speaking of an ‘industrious revolution’ that began shortly before the industrial one and continued as industrialization began to spread (de Vries 2008). The productivity of threshers seems to have roughly doubled from the 14th century to the 19th century, a period during which there were no great technological changes in the method used to thresh grain (1987). Hours worked per week in London probably increased by some 40% over the second half of the 19th century, with people working some 19 more hours per week at the end of the period than they had been half a century earlier (see again de Vries 2008). And an analysis of time expenditure in different cultures found that people in commercial societies worked an average of 10-15 hours per week more than people in subsistence economies (Bhui et al. 2019).

There is some evidence that suggests that Protestantism may have contributed to the rise in Western industriousness alongside other factors. The higher the percentage of Protestants in a country (both today and in 1900), the better its citizens typically perform on a standard test of self-regulation (Casey et al. 2011). In Germany, people from traditionally Protestant areas typically work longer hours than people in traditionally Catholic areas (Spenkuch 2017). In Switzerland people in traditionally Protestant areas are more likely to vote against measures that would mandate shorter workweeks, lower the retirement age, or mandate longer holidays (Basten and Betz 2013).

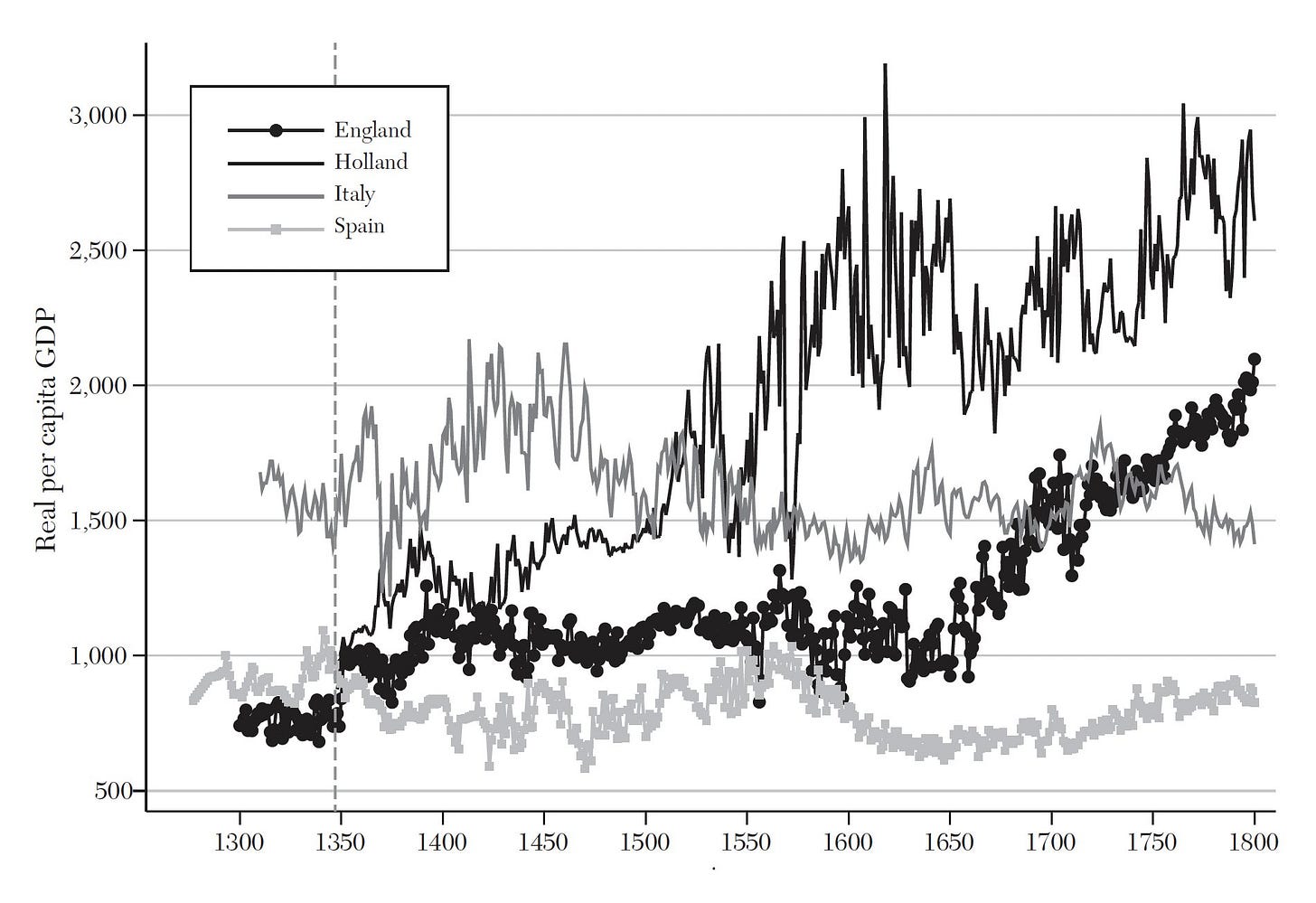

But if what we are seeking to explain is why northern Europe became richer than southern Europe from the early modern period on (the so-called ‘little divergence’: van Zanden 2009), the most important mechanism through which Protestantism helped stimulate growth may not have been industriousness but literacy. Distance from Wittenberg, the epicentre of the Reformation, predicts literacy in Prussian counties in the late 19th century, suggesting that a greater dosage of Protestantism boosted reading and writing (likely through the Protestant emphasis on sola scriptura or scripture as the sole true path to understanding God’s will: Becker and Woesmann 2009). Areas of India with more Protestant missionary activity, like Kerala, also had higher literacy rates in the same period (Ferguson 2011, 261-262). Protestantism was also associated with more schools and printing-presses, which obviously played a role in the promotion of literacy (see again Becker and Woesmann 2009, Ferguson 2011, 261-262).

Some of the developments we have discussed so far - especially the weakening of kin-networks, the spread of markets, and the rise of literacy - may also have encouraged more individualistic and abstract ways of thinking about morality and politics. People from WEIRD societies are more inclined to follow abstract rules even at the expense of their own interests or those of their friends and family-members (Fisman and Miguel 2007; Gätcher and Schulz 2016). They trust strangers more (that is, they have higher levels of ‘generalized trust’: Thöni 2017); see intentions as more important when it comes to judging people morally (Barrett et al. 2016); and they exhbit more analytical than holistic styles of thinking (Henrich 2020, 52-55). Arguably, they are more likely to see law in terms of abstract principles; the interpretation of Roman law in terms of divinely-sanctioned ‘divine law’ by 12th-century jurists may have been a crucial step in this direction (Berman 1983). Finally, they are more inclined to attribute intellectual discoveries and advances to individuals rather than societies or lineages (Wootton 2015).

These tendencies toward individualistic and abstract ways of thinking likely played a role in the European scientific revolution (c. 1530-1789) alongside other factors such as economic growth, inter-state competition, the increase in literacy, and the proliferation of learned societies (Mokyr 2002; Ferguson 2011, 50-95). Did they also underpin the rise of modern liberal democracy?

Probably. Certainly, democracy is strongly associated with economic growth, even if that now seems to be due more to the stability of wealthy democracies more than to any simple causal relationship between democracy and economic development (Przeworski et al. 2000, effectively updating Lipset 1960). Between 800 and 1500, the longer experience that cities had of the Christian church (dated from the appearance of a local bishop) the more likely they were to have some representative institutions (Schulz 2022). In the contemporary world, countries with more intensive kinship structures are ranked lower in international rankings of democracies; the rate of cousin-marriage alone (which, as we have seen, is mediated by church exposure) accounts for about half the variance in their democracy scores (Schulz 2022). In Europe, citizens whose families migrated from more kinship-intensive societies participate less in politics (voting less, for example, and signing fewer petitions: see again Schulz 2022). In contrast, citizens in areas of Switzerland with a longer history of participatory government are more cooperative today, likely making them more inclined to support and make use of participatory institutions going forward (Rustagi 2022).

Modern – once predominantly Western – science was not simply inherited from the ancient Greeks or Romans (or from the Islamic Golden Age, Tang China, or ancient India, for that matter). All of these cultures contributed to later societies’ understanding of the world, including early modern Europeans’. But the European scientific revolution was marked (in contrast to the Renaissance) more by a rejection of classical understandings than by a re-discovery of them. The overthrow of Aristotle and Ptolemy’s model of the universe by Galileo, Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler and others is only the most spectacular example. It can be argued that there was a scientific or proto-scientific mindset implicit in some Greek texts, and that this helped early modern thinkers along in finding their way to a fuller conception of scientific methodology; we might wonder if Bacon’s new organum (method) would have been possible without Aristotle’s ancient organon. If there is only a weak sense in which ancient Greek science (and Roman technology) contributed to modern Western science directly, though, the conditions may have been laid for its emergence by the processes we have just surveyed - processes in which Christianity (which itself emerged out of the Greco-Roman world) played a significant role.

Something similar could be argued when it comes to liberal democracy. Once again, modern Westerners did not simply inherit democracy from the classial Athenians; there is no unbroken line of transmission from the bema (the speaker’s platform in the Athenian assembly) to the Beehive. The Western philosophical and literary tradition was largely hostile to democracy, at least until the middle of the 19th century, when the slow and uncertain rise of British democracy began to prompt thinkers like George Grote and John Stuart Mill to take a second (and more charitable) look at ancient Athenian democracy (Roberts 1994; Kierstead 2014). When democratic or republican arguments were made – quite rarely before the early modern period, but more frequently thereafter – they did tend to draw on arguments from high-prestige Greek texts; Grotius’ contractarian account of the sate, to cite just one example, seems to owe something to Plato’s Crito (50e; for further examples see Flaig 2013, 451-452). Democratic practices like sortition similarly seem to have drawn some encouragement or legitimation from Greek texts, even if they were not directly inspired by them (Kierstead 2021b). On the whole, though, it was probably structural factors – both economic ones and the sociological ones we just surveyed – that played the most important role in bringing modern representative institutions into being. And again, these sociological factors were underpinned to some extent by Christianity, which emerged out of the confluence of Greek and Jewish cultures in Roman Palestine.

Some Concluding Thoughts

What I have tried to do in this paper is very briefly give a sense of recent research on the West and Western history. What it suggests is that modern (that is, industrialized) Western societies are unusual, and that their unusualness has deep historical roots. Some aspects of WEIRD societies can be traced all the way back to classical Greek and republican Roman times (monogamy); others (especially marriage and family norms) developed in tandem with the Christian church – which was itself, to repeat this now often-forgotten fact one last time – an ancient Greco-Roman institution. Still others (literacy, science) only fully emerged in the wake of the Protestant Reformation – though here, too, we should remember that the revolutions put in motion by Luther, Calvin, Zwingli and their peers were founded on revolutionary ways of reading ancient Greek, Latin, and Hebrew texts.

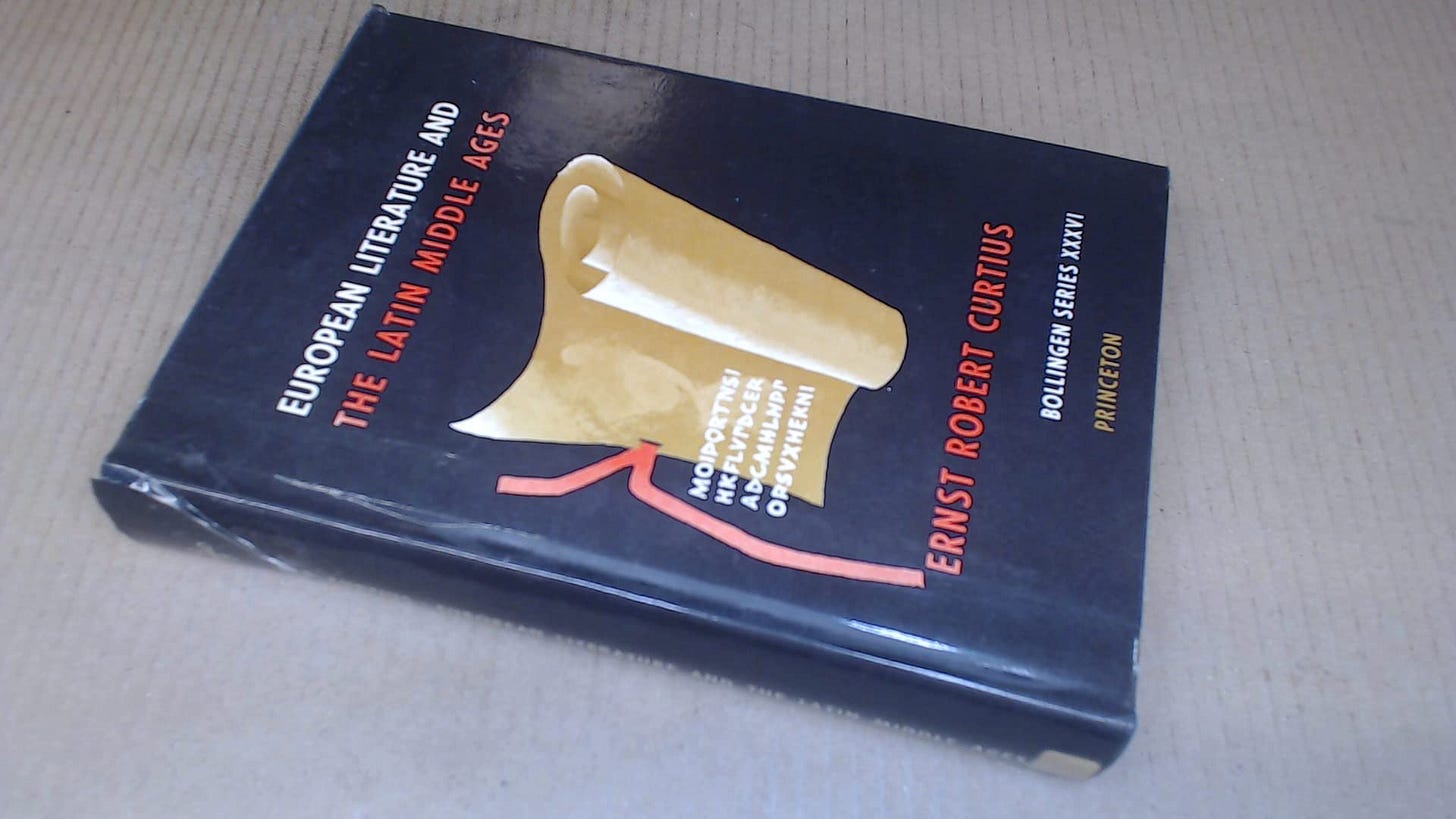

I began with only the briefest mention of the the influence of Greco-Roman art, literature, and philosophy on subsequent high culture in the West (though readers who want to learn more about the continuing influence of Latin letters, for one thing, after the fall of Rome could do worse than begin with Ernst Robert Curtius’ classic European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages). I presented that argument only very summarily both because the case for classics as Western cultural literacy has become weaker in recent years as Western high culture itself retains less of a place in curricula, and because the recent research I draw on here (stemming mainly from fields like economic history, anthropology, and psychology) may be less familiar to readers, including classicists – and therefore more worth showcasing.

If the evidence I have adduced here is unfamiliar to classicists, that may be partly because of a recent turn within US classics especially against the whole idea of Western civilization, which is now widely viewed as nothing more than a ‘social construct’ or a ‘narrative’ (MacSweeney 2023). But whether or not a certain story about the past is merely a story and has no substance behind it is something that can only be adjudicated once we have thoroughly examined the evidence. As I indicated above, some of the more traditional, ‘naïve’ assertions about the Western tradition do not seem to be well supported by evidence. But there is now a host of new evidence drawn from a range of fields that Western societies have in fact been influenced by a number of historical trends going back to late antiquity at least.

If most classicists continue to ignore this research, it will simply go on being done in departments of anthropology, political science, and economics as classics departments continue to contract and disappear across the Western world. That would be a pity, not least because this new research, even if it does not uphold more traditional views of Western civilization in every respect, can nonetheless provide us with an empirically grounded, methodologically sophisticated, and, above all, positive account of the continuing importance of our field. The point of this piece is not to completely displace other arguments for classics; it may also, for example, help students deal with evidence, and to think about the world in a more inter-disciplinary way (with classics encompassing literary criticism, history, philosophy, art history, historical linguistics, and other fields). But none of these arguments really tell us why students should be spending their time dealing with this particular evidence, and this particular form of inter-disciplinary inquiry.

Western societies, like all societies, have a history. To think that the history of Western societies is important is no more ‘white supremacist’ than valuing Maori history is Polynesian supremacist. Ancient Greece and Rome simply did, in fact, exert an enormous influence on subsequent Western culture and society, one that continues to this day. This is not a statement of defiance but a simple descriptive statement about global cultural history. There seems no doubt that some elements of this Western cultural package (literacy, modern science, liberal democracy) are positive and have had a largely positive influence on the world. Others – especially the enormous lead in military power that the West obtained around the time of the industrial revolution – are more morally ambiguous. And some elements of the WEIRD heritage seem clearly negative: Westerners’ greater propensity to see things as individual property; their greater alienation from the kin structures in which humans spent most of their evolutionary history; the greater tendency of people from a Protestant background to guilt and even suicide (Becker and Woessmann 2016).

The point is not that everything in our Western heritage is uncomplicatedly wonderful, but that understanding the past, and how it retains some influence on the present, is a vital undertaking for any society – not least ones, like New Zealand, whose institutions and mainstream culture were imported relatively recently. Of course citizens of our Western, multicultural democracies should learn about the heritage of major ethnic minority groups as well, including (in New Zealand) Maori and Pacific Islanders. But Western countries are also Western and, given what the recent research shows about the surprising persistence of culture through centuries and even millennia of history, they will almost certainly remain Western to some extent for some time. This is one of the reasons – a now often-overlooked one, and arguably the most important – that people in Western societies today should continue to study the cultures of the Greco-Roman world, however distant, and however irrelevant, they might at first seem.

Works Cited

Agneman, G., and Chevrot-Bianco, E. (2022). Market participation and moral decision-making: experimental evidence from Greenland. The Economic Journal 133 (650), 537-581.

Barrett, H., Bolyanatz, A., Crittenden, A., Fessler, A., Fitzpatrick, S. ... and Laurence, S. (2016). Small-scale societies exhibit fundamental variation in the role of intentions in moral judgment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113 (17), 4688-93.

Basten, C. and Frank Betz (2013). Beyond Work Ethic: Religion, Individual and Political Preferences. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 5 (3), 67-91.

Becker, S. and Woessmann, L. (2009). Was Weber wrong? A human capital theory of Protestant economic history. Quarterly Journal of Economics 124 (2), 531-596.

Becker, S. and Woessmann, L. (2016). Social cohesion, religious beliefs, and the effect of Protestantism on suicide. Review of Economics and Statistics 100 (3), 377-391.

Berman, H. (1983). Law and Revolution: The Formation of Western Legal Tradition. Harvard University Press.

Bhui, R., Chudek, M., and Henrich, J. (2019). Work time and market integration in the original affluent society. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116: 22100-22105.

Bryant, M. (2021, July 31). Latin to be introduced at 40 state secondaries in England. The Guardian.

Casey , B., Somerville, L., Gotlib, I., Ayduk, O., Franklin, N., Askren, M…. and Shoda, Y. (2011), Behavioral and neural correlates of delay of gratification 40 years later. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (36), 14,998-15,003.

Clark, G. (1987). Productivity growth without technical change in European agriculture before 1850. Journal of Economic History 47, 419-32.

Clark, G. (2007). A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World. Princeton University Press.

de la Croix, D., Doepke, M., and Mokyr, J. (2018). Clans, guilds and markets: apprenticeship institutions and growth in the pre-industrial economy. Quarterly Journal of Economics 133, 735-75.

de Vries, J. (2008). The Industrious Revolution: Consumer Behaviour and the Household Economy, 1650 to the Present. Cambridge University Press.

Ferguson, N. (2011). Civilization: The West and the Rest. Penguin.

Fisman, R. and Miguel, E. (2007). Corruption, norms, and legal enforcement: evidence from diplomatic parking tickets. Journal of Political Economy 115 (6), 1020-1048.

Flaig, E. (2013). Die Mehrheitsentscheidung: Entstehung und kulturelle Dynamik. Schöningh.

Gächter, S. and Schulz, J. (2016). Intrinsic honesty and the prevalence of rule violations across societies. Nature 531, 496–499.

Gurven, M., van Rueden, C., Massenkoff, M., Kaplan, H., and Lero Vie, M. (2013). How universal is the big five? Testing the five-factor model of personality variation among forager-farmers in the Bolivian Amazon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104: 354-70.

Gettler, L.T., McDade, T.W., Fernail, A.B., and Kuzawa, C.V. (2011). Longitudinal evidence that fatherhood reduces testosterone in human males. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108: 16194-99.

Henrich, J. (2020). The Weirdest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous. Allen Lane.

Holland, T. (2019). Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind. Basic Books.

Huntingon, S.R. (1996). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon and Schuster.

Kierstead, J. C. (2014), The Character of democracy: Grote’s Athens and its legacy. In D. Piovan and G. Giorgini (eds.) Brill's Companion to the Reception of Athenian Democracy From the Late Middle Ages to the Contemporary Era (pp. 220-270). Brill.

Kierstead, J.C. (2021a) No, classics shouldn’t ‘burn.’ Chronicle of Higher Education. February 23.

Kierstead, J.C. (2021b). Is democracy Western? The case of sortition. Medium. April 25.

Lape, S. (2003). Solon and the institution of the “democratic” family form. Classical Journal 98, 117−139.

Lipset, S. M. (1960), Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics. Doubleday & Company.

MacSweeney, N. (2023). The West: A New History of an Old Idea. Penguin.

Mokyr, J. (2002). The Gifts of Athena: Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy. Princeton University Press.

Ogilvie, S. (2019). The European Guilds. Princeton University Press.

Pfeiffer, R. (1968). History of Classical Scholarship: From the Beginnings to the End of the Hellenistic Age. Oxford University Press.

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J. and Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950-1990. Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, J.T. (1997). Athens on Trial: The Antidemocratic Tradition in Western Thought. Princeton University Press.

Rustagi, D. (2022). Historical self-governance and norms of cooperation. CeDEx Discussion Paper Series, No. 2022-04.

Scheidel, W. (2009). A peculiar institution? Greco-Roman monogamy in global context. History of the Family 14: 280-91.

Schmidt, B. (2018, August 23). The humanities are in crisis. The Atlantic.

Schulz, J. (2022). Kin networks and institutional development. Economic Journal 132, 2578–2613.

Spenkuch, J. (2017). Religion and work: Micro evidence from contemporary Germany. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 135 (C), 93-214.

Thöni, C. (2017). Trust and cooperation: Survey evidence and behavioral experiments. In P. Van Lange, B. Rockenbach, and T. Yamagishi (eds.) Social dilemmas: New perspectives on trust (pp. 155-72). Oxford University Press.

van Zanden, J.L. (2009) The Long Road to the Industrial Revolution: The European Economy in a Global Perspective, 1000-1800. Brill.

Verger, J. (1991). Patterns. In H. de Ridder-Symoens (ed.) A History of the University in Europe: Universities in the Middel Ages (pp. 35-68). Cambridge University Press.

Wootton, D. (2015). The Invention of Science: A New History of the Scientific Revolution. Penguin.

![Legality of Polygamy Worldwide.

[[MORE]] cookiesmasher747:

Something I learned while researching this - while polygamy is legal in 58 nations, polyandry (a woman being married to multiple husbands) is illegal in every country in the world. Legality of Polygamy Worldwide.

[[MORE]] cookiesmasher747:

Something I learned while researching this - while polygamy is legal in 58 nations, polyandry (a woman being married to multiple husbands) is illegal in every country in the world.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!UMVd!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F814d1fac-13ad-4ecf-bbdb-4e8e621b57f9_1280x690.png)

Fascinating connections. Thanks for sharing this. I suppose you can’t say everything in an article but I wonder if the picture laid out here covers over the conflict between paganism and Christianity rather than seeing them as comfortable allies. And the conflict between Protestantism and Catholicism. (Protestants famously destroyed and removed anything that felt Catholic to them.) The Enlightenment wanted to break the Church. The French Revolution was an outgrowth of Western Civilization and yet it was also an attempt to wipe the slate clean. In other words, the attempted destruction of the pillars of Western Civilization is one of Western Civilization’s greatest traditions. Perhaps its greatest one?

Perhaps the best article on the conception of Western civilization vis-à-vis its relationship with the ‘Classics’ that I’ve read on Substack!

Understanding the ancient Greeks isn’t about skipping and jumping over thousands of years to directly pledge a civilizational debt (in democracy, science, morality, etc) to a remote, elite culture in ancient Greece. This more anthropological approach illuminates how peculiar cultural practices in marriage, kinship networks, and non-kin institutions present since antiquity provide a base social infrastructure upon which the transmission, critique, and inculcation of seminal ideas of the West could flourish and continually transform. Well done!