Citational Justice and the Growth of Knowledge

Recently I received an email from Iona Italia, editor of Areo magazine, informing contributors that this fantastic liberal outlet would be wrapping up operations, and advising us to republish our posts somewhere else - on Substack for example. I’ve decided to take her advice, and re-post my half-dozen or so Areo pieces - including two articles that appeared anonymously - on here.

This is the fourth piece I published on Areo, on December 19th 2019. I I had originally planned to write it with a colleague from Heterodox Academy, but they dropped out at an early stage, with the first-person plural pronouns (we, our) one of the only remnants of this planned collaboration.

Finally, I originally published this piece anonymously because I was afraid that it would negatively affect my Classics career. Now that I have been given notice by my university, though, I have decided to post it here under my name.

The purpose of research is to grow our knowledge of the world: whether the focus is quarks, ancient Chinese texts or the income trajectories of US immigrants. This focus on knowledge means that scholars have traditionally prioritized the accuracy and usefulness of claims about the world more than, for example, the past behaviour or demographic profile of the people making those claims.

One tool that scholars use is citation. Scholars cite for a range of reasons. Citations can be used to explain why researchers have undertaken their work (Many studies have examined the effect of exercise on mental health; we look at the effect of weight training on anxiety in particular.) They can link specific studies to larger questions (Our study is part of a broader body of work about the effects of exercise on mental health) or to specific studies on related topics (On endurance exercise and anxiety, see Long and van Stavel 1995). Perhaps most fundamentally, citations can support concrete claims; they make clear where these claims come from, and allow the reader to check their sources (Endurance training has been found to enhance the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor: Seifert et al. 2009).

Scholars also occasionally cite for reasons that are less tightly bound up with the growth of knowledge. They may simply want to show their familiarity with the major works in the field (this can result in a parade of citations, some of which may have little to do with the topic at hand). They may cite scholars they’re on good terms with as a gesture of friendship or goodwill. This can shade into the kind of personal praise that is often found in the acknowledgments section of books.

Personal praise of this sort likely accounts for a tiny percentage of total citations. Citations are used overwhelmingly to situate work within an existing literature—usually by indicating acceptance or dissatisfaction with a line of thought. People who understand how citations are used tend to take for granted that citing someone’s work isn’t like writing a personal reference for her, and that citations aren’t meant to model any sort of ideal demographic balance.

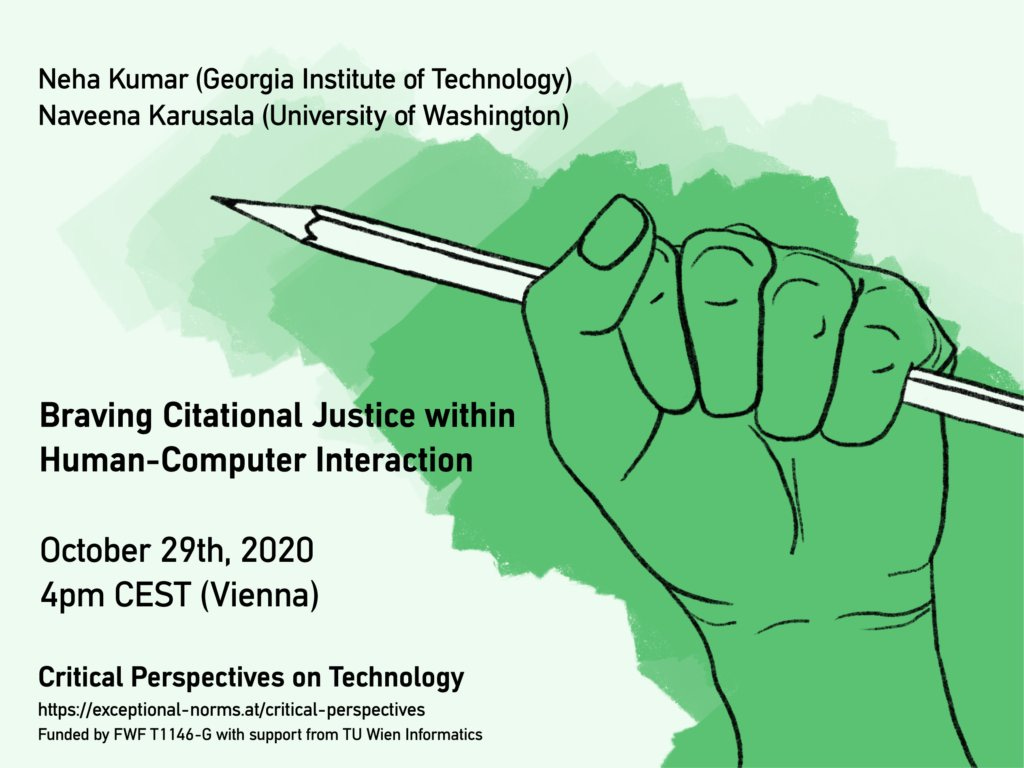

Recently, however, a movement has grown up that invites scholars to rethink the way we cite. This movement for citational justice is motivated by three main concerns. First, a concern for distributive justice: the idea that the goods that flow from being cited should be apportioned equably among people of different ethnicities, genders and sexualities. Second, a concern that scholars who have done good work get cited as much as they deserve, even in the face of possible biases (especially against ethnic minorities and women). We call this second concern citational justice as citational fairness. Finally, there’s a concern that individuals who’ve done wrong shouldn’t continue to have a major presence in citations: this takes us into the sphere of retributive justice.

At least two of these concerns are evident in this short talk at the Society for Classical Studies (SCS) annual conference by Professor Sarah Bond of the University of Iowa. The movement has a presence in other disciplines, too: at this year’s American Sociological Association conference, #citeblackwomen was trending on Twitter and the same hashtag appeared in Twitter threads for the American Psychological Association meeting. Bond’s comments provide a convenient encapsulation of the citational justice movement by a scholar who is an influential figure in her field.

Distributive Justice

Bond is interested in what she calls “lifting as we climb,” a phrase she attributes to the NAACP:

If you cite women, if you include women of color in particular, that is how we are going to climb, and I think we can apply that to the entirety of the SCS to say that moving away from only citing Theodor Mommsen, from only citing William Harris, from only citing various scholars who are part of the canon and diversifying our footnotes and thinking about how to include more people rather than following the same path that we’ve been led to our entire career as classicists.

When Bond talks about “diversifying our footnotes” and “thinking about how to include more people,” she’s advocating citing more non-white people and women, i.e. including more people from particular groups in footnotes.

This appeals to an ideal of distributive justice: that goods and benefits should be apportioned equably. The idea that citations are a kind of good has a lot to say for it. Scholars are increasingly evaluated in terms of their citations and this can have effects on their promotions, ability to obtain positions at prestigious institutions, invitations to high profile events and so on. Wouldn’t it be better if citations were shared around more, especially in fields (like Classics) where they’re dominated by white men?

The main problem with this is that it would make it unclear why a specific citation was there: because the work referred to is actually useful, or for the purposes of distributive justice? That could have the unintentional knock-on effect of increasing cynicism about non-white and female scholars, since it would lead to a lot of citations that have clearly been included primarily for political reasons, rather than scholarly ones. Scholars will also have to weigh up how many scholarly citations they can afford to put in if they want a total citation count that meets the requirements of distributive justice.

What are the demands of distributive justice when it comes to citations? Should the breakdown of total citations match the demographic breakdown of the local area, the country or the world? Which country should count—the country the piece was written in, published in, or the country the author is from (assuming there’s only one)? Which demographic characteristics should be taken into account—ethnicity and gender, sure, but what about language, religion or political affiliation? And which ethnicities, genders, languages and so on should be on the list? Should this apply to single articles or books or entire careers? If I cite more black women in one piece, can I cite more white men in another?

Then there’s the problem of determining which demographic categories scholars should be included in. A scholar’s sex or ethnicity may not be obvious. Determining in which category to put academics with sex-ambiguous names like Hilary Putnam might not take much time, but it will take some, time that will be multiplied by a large number of citations. The case of trans academics like Deirdre McCloskey raises further complications, since works they produced while they identified as one sex may be deemed to be more or less deserving of citational justice than other works produced by the same person. Ethnicity can be an even more slippery notion: how do we decide which categories we place scholars from the past in, especially when the categories we’d prefer to use don’t line up with the way they thought about themselves?

Perhaps Bond’s advocacy of diversifying our footnotes reflects a concern with intellectual diversity: classicists should cite more scholars who aren’t white men because more demographic diversity can bring greater diversity of ideas.

This would move us outside the realm of justice per se, but that’s only a superficial objection. A more serious issue is that the diversity argument brings up many of the same questions as the distributive justice argument. Which demographic characteristics should we be seeking to diversify? Won’t it cost some time for scholars to find out the racial characteristics of everyone they cite, and, if so, is this a cost we want to impose every time someone writes a footnote? And so on.

Let’s return to what Bond says about “moving away from only citing Theodor Mommsen, from only citing William Harris, from only citing various scholars who are part of the canon.” We’ll pass over the claim that classicists only cite canonical scholars, since this is probably a rhetorical exaggeration. And anyway, classicists do tend to cite canonical scholars more often.

Is this a problem and, if so, why? Two possible objections are that this practice doesn’t share citations around equably, and that it leads to a lack of diversity (both demographic diversity and diversity of ideas). This second concern isn’t really a matter of justice, but even if it were, it’s not clear that it would be a matter of citational justice.

Why not? One reason why we might not be troubled by the fact that classicists cite canonical scholars more often than others is if there was a reasonably robust relationship between the scholars who tend to be cited and the quality and quantity of their scholarly output. Now, this set of scholars might be less diverse than we might have hoped, either from the point of view of distributive justice, or from that of diversity (or both). But if so, that might reflect perfectly just and diverse citing practices, applied to a set of scholars that isn’t particularly varied in demographic terms.

Behind these concerns for distributive justice and diversity, then, we can sometimes glimpse another concern. This stems from the apparent assumption that there must be more works out there that are worth citing and that weren’t produced by white men. If they haven’t been cited more, it must be because of prejudice against women and ethnic minorities. And that would be unfair.

Citational Justice as Citational Fairness

In his Theory of Justice, John Rawls sometimes speaks of “justice as fairness.” That scholars who produce high quality, useful work deserve to be cited seems fair. Proponents of citational fairness claim that their main concern is that good quality work is being overlooked, and thus lost from the scholarly conversation.

Concerns for distributive justice and diversity appeal entirely to values, which can’t be shown to be false. Citational fairness makes an empirical claim: that certain works aren’t cited mainly because of prejudice. This is more difficult to prove.

A citational fairness version of Bond’s argument would run along the following lines: some people are cited less than others in Classics, and this is to a significant extent not a result of the quality or quantity of their work, but of considerations that militate against women and non-white people.

Does this claim hold up? Let’s start with the idea that some people are cited less than others in Classics. That seems to be true. Journal articles in Classics are overwhelmingly produced by white people as Dan-el Padilla Peralta demonstrated during the same panel that Bond was part of.

Is it clear that this is a result of sexism and racism? We’re sceptical, since Classics journals tend to receive anonymous submissions, and it’s hard to see how editors would even be aware of an author’s sex or ethnicity. We can’t be completely sure why white people preponderate, but Classics still has a much stronger presence in parts of the world where there are more white people.(The country with the most secondary students studying Latin and Greek, for example, is Italy, which is more than 92% white.)

In any case, this brings us outside of the realm of citational justice, and into the realm of what might be called publicational justice. Because more Classics journal articles have been written by white men, we’d expect citations to also be quite white and male, even in the absence of prejudice at the point of citing.

The assumption, then, that citations in Classics must reflect prejudice against a large number of high quality, but unfairly overlooked, works by non-white classicists may be false. Of course, non-white classicists (not least Professor Padilla Peralta himself) have produced a number of high quality works. But, in terms of numbers, they may simply be overwhelmed by the demographic profile of Classics as a field both in the past and (to a lesser and decreasing extent) in the present.

None of this implies that Classics shouldn’t seek to change its demographic profile. Anyone who believes in the value of his field should be eager to see young people of all backgrounds, in all parts of the world, take it up; and anyone who cares about her field’s future will look forward to hitherto underexplored perspectives.

But not every field will be equally attractive to everyone in every part of the world. The study of Greco-Roman antiquity will, for the foreseeable future, probably prove more appealing to people in Europe and the West than in other parts of the world. Since these areas are still largely majority white, that may mean that journal articles and citations in Classics will also be more white than not for a while yet.

We should also remember that the value of spreading the word about the field isn’t dependent on the idea that the field is tainted with prejudice. You might well think it would be nice if there were more citations of important works by scholars who aren’t white and male. But it’s possible to think that even if you don’t believe that the current patterns of citation are a result of racism and sexism.

Retributive Justice

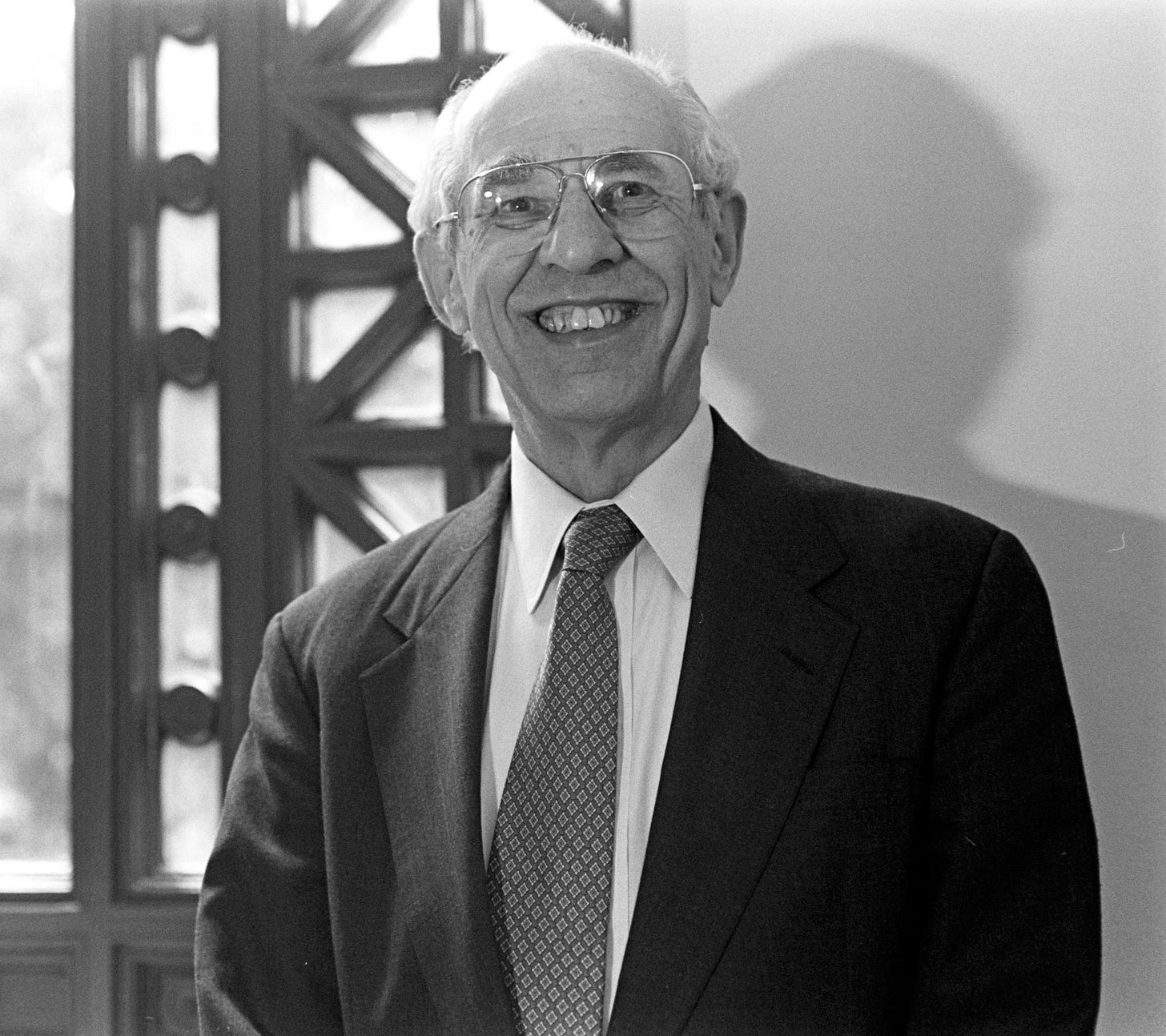

One final concern that emerges from Bond’s comments is the idea that we should pay less attention to works produced by writers whose morals we question. This is a concern with retributive justice. Bond gives the example of William Harris, a widely cited historian who was, until recently, a professor at Columbia.

Most of Bond’s audience would have been aware of Harris’ recent retirement in the wake of a harassment lawsuit, and would probably have understood her to be pointing to this as the reason to cite other scholars. In any case, Bond makes her concern for retributive justice clear earlier on, when she states that she no longer cites influential digital humanist Franco Moretti because of allegations against him.

The basic idea of retributive justice is simple: people who’ve done wrong should be punished. Few people would object to the idea that someone who’s been found guilty following an appropriate legal process should be subject to mandated penalties. There’s also nothing preventing individual citizens and scholars from imposing social sanctions on people. But the idea that these considerations ought to enter into scholarly citation practices is problematic.

Moral probity doesn’t have an obvious relationship to the utility of a scholarly or scientific contribution. Major figures in intellectual history, from Thomas Jefferson to Erwin Schrödinger, made choices that we would rightly condemn today. In a world in which citations are distinct from moral approval, citing their work without signaling approval of their behaviour is easy. However, under a retributive justice model, the act of citation might be interpreted as tacit support for an author’s misdeeds.

Subjecting authors to a purity test raises a number of questions. Who decides which infractions merit sanctions? Is there a statute of limitations on transgressions? Moreover, what are the implications for scholars doing the citing? Are graduate students going to be responsible for performing an ex ante exculpatory search for background information on anyone whose work they might want to refer to in a footnote? That might be possible (if burdensome) in the case of thinkers whose personal behaviour has become a matter of public knowledge. But what about those we know little about?

Seeing citations as a place for retributive justice also raises some questions about how and under what conditions we can carry out retribution in a just way. Most countries have legal codes, one of whose major concerns is to define what kinds of retribution can be imposed, and under what conditions. Laws also often seek to separate the kinds of social sanctions that can be applied freely (ending a friendship, say) from professional and legal penalties, which usually demand some amount of due process and a higher burden of proof.

Now, maybe dropping someone from citations is best seen as a kind of social sanction, like ending a friendship. If it is, though, it’s the kind of social sanction that has knock-on effects on others, since, if Bond doesn’t cite William Harris because of harassment charges, people reading her work might be deprived of some influential and important scholarship on a given topic. So maybe it’s more like not inviting someone to a party, even though you know your fellow guests might profit from his presence.

But if citations are a kind of good, removing someone from a list of acceptable references looks more like a professional sanction, like being struck off the medical register. In extreme cases, if a scholarly community refuses to mention a scholar at all any longer, this can amount to erasure from the field, or, as the Romans would have put it, a damnatio memoriae. But professional sanctions usually demand at least some form of procedure; and something as serious as removing someone from the field entirely (even on a purely intellectual level) would seem to demand a very robust process indeed.

Bond isn’t compelling the entire field not to cite William Harris or Franco Moretti. Yet, it’s easy to imagine how an atmosphere might emerge in which citing either of these scholars is seen as slightly suspect. Why is he citing William Harris? someone on a job committee might ask. Is it because he approves of the kind of thing I’ve heard Harris was up to? We might very quickly find that citing a particular scholar’s work is beyond the pale.

This process would be extra-legal. Granted, Harris did go through a judicial process, and received the due penalties. But we doubt that any judge or jury instructed that his works should no longer be cited. And what about a scholar who’s simply been accused of something, but hasn’t yet been accorded due process? Does it make sense to mark whatever work he’s produced as tainted, not to be discussed in the polite company of scholarly footnotes?

Bringing retributive justice into citations, then, can approach a kind of vigilantism. And it introduces extraneous considerations into the practice of citing. Citing Schrödinger shouldn’t really be seen as an act of moral approval, since citations aren’t concerned with moral purity.

The argument centering on distributive justice is vulnerable to the criticism that it introduces considerations that are completely alien to the practice of citing. But (as we saw above) advocates of citational justice sometimes make a slightly stronger claim: that some scholars deserve to be cited more but aren’t, probably because of prejudice.

When you look at citations as a matter of retributive justice, though, this kind of move isn’t available. Proponents of distributive justice appeal to a plausible mechanism that was a result of bias in the citing process itself. We do want fewer white men to be cited!, they might say. But that’s not because we want to randomly introduce a scheme of distributive justice into citing practices—it’s because prejudice in favour of white men actually biases the practice of citing!

Let’s try this with retributive justice. Imagine we told Bond, You’re randomly introducing retribution into citing! She might reply, No, I’m just making sure citation is working properly, and up till now there’s been a bias in favour of people who’ve done bad things. But why would there be a bias towards citing people who’ve done bad things? The idea that physicists cite the Schrödinger equation more because of his sexual misdemeanors doesn’t make much sense. In the case of scholars like Harris, who were widely cited for decades before allegations of impropriety came to light, it doesn’t even seem possible that improper acts helped drive his citation count. After all, virtually nobody heard the allegations until a long time afterwards.

Introducing retributive considerations smuggles in something which doesn’t have anything to do with the scholarly practice of citation. It also makes citing into a way of arbitrating claims of justice, something to which it’s gravely unsuited.

Bond also brings up the example of Basil Gildersleeve (1831–1924), founder of the prestigious American Journal of Philology and the author of a number of influential works on the Latin and Greek languages, who was also a confederate apologist. Here, of course, the concern can’t be for retribution in any ordinary sense, since Gildersleeve has long ago departed this earth and thus can’t be subjected to sanction. What’s going on here?

We might think that what’s motivating this is a cosmic or transcendent idea of retributive justice: Gildersleeve may be dead, but now he’s at last getting a slice of what he had coming. But should scholars really be privileging this sort of religious anathema, especially at the cost of leaving students and readers in ignorance of a very significant figure in classical philology?

Bond’s comments suggest that her concern is more that citing past defenders of slavery might create a climate that’s unwelcoming to black students and scholars. But if the assumption is that everyone who cites Gildersleeve agrees with his views on slavery, that is clearly false. It would be very difficult—perhaps impossible—to find a classicist employed at an American university today who agrees with Gildersleeve’s take on racial issues.

The only other possible concern that leaves is that black students today will be unable to cope with being exposed to books on classical languages written by a long-dead scholar who also advocated for slavery. That would be an extremely patronizing assumption to make about young black classicists. It might also signal that they were too weak to deal with texts written by writers who were in favour of slavery, a category that includes virtually all the authors of Greco-Roman antiquity.

Citations as Citations

To sum up, proponents of citational justice can be motivated by any of three main considerations. They may be disturbed by the uneven distribution of citations, which offends their sense of distributive justice, and produces a leaderboard of scholars that they find insufficiently diverse. Or perhaps their main issue is that this insufficiently diverse leaderboard must be a result of prejudice, and so is unfair. They may also be tempted to make use of citations as a form of retribution against scholars they think have done bad things.

There is an alternative attitude to citation: one we call citations as citations. This ideal (the traditional approach) involves scholars citing works they think are helpful to the inquiry they’re engaged in. They may find them helpful in providing background; in linking their writing to other specialist literatures; or in allowing readers to double-check a claim.

One key feature of this approach is that citations are not viewed as anything else. This relieves students and scholars of having to come to a comprehensive moral judgment about every scholar they cite. It absolves them of the statistical analysis they might otherwise be under pressure to do in order to ensure that their citations match the demographic distribution of whichever country they happen to be in. And it allows them to focus entirely on a task that has brought great benefits to all – the task of growing knowledge.